This essay is free for all, but the recipe at the end is available just for paid subscribers

Have you heard of Bantayan? It’s a small island in the Philippines, more specifically just off the northern tip of Cebu, sitting astride the deep blue Tañon Strait. You might have seen packs of dried fish from Bantayan in your local Filipino shop - the island is known in particular for its buwad - and maybe you’ve read an article extolling its white sandy beaches as an alternative to the more popular and developed Boracay.

But I’ll understand if this tiny coral-limestone island has never come onto your radar before. Even the Spanish, when they first came across Bantayan and its neighbours, considered them quite unremarkable - “all low and very small”, was the verdict written down by Fray Juan de Medina in 1630.

So I do wonder what crossed the mind of the church bureaucrat, halfway around the world in the Vatican, who received a request - in 1824, 1829 or 1840; numerous dates float around the internet - to grant an exemption for Bantayanons to eat meat during the days of fasting in Holy Week.

Hold up a moment. What? (That’s not my impression of said church bureaucrat).

It does sound like something made up: that people in Bantayan have permission from the Pope to eat meat on Good Friday. But lo and behold, the Parish of Saints Peter and Paul proudly announces that they have a copy of the papal indult in their possesion and on display in the parish museum.

The above is a photo I took outside of the Bantayan Parish Convent and Museum in December 2022; it was unfortunately closed when we visited. The sign states:

Inside the museum is a copy of the Papal Indult that allowed Bantayan parishioners to eat meat during the Holy Week, on the condition that abstinence is carried out on some other days

Why the request though? As per the story I was told, Bantayanons are a particularly devout (and superstitious) people: during Holy Week, and particularly on Good Friday, few if any fishermen ventured out to sea in search of catches, because they considered it bad luck to be risking their lives whilst Jesus was dead and buried and God mourning; who would be out there protecting them? If they were to get injured, particularly whilst Jesus was in the grave, local beliefs stated that the injury would be fatal or at the very least life-changing. I am reminded of the numerous “God is my Co-Pilot” (and other similarly-themed) signs abounding in the Philippines, invoking divine protection for those who partake in another dangerous trade: being a jeepney or tricycle driver.

Since fish was the main food, and since the fishermen were not out catching fish, and since they were also abstaining from meat, there was a real concern that the locals were not eating anything at all during Holy Week. The local priest, Don Doroteo Andrada Del Rosario, therefore found it easier to petition for the locals to eat meat, than to shift their superstitions about fishing.

Conversely, Rappler relates the story that Bantayanon fishermen were fishing too much during Holy Week, to obtain that much-needed food; to get them to actually stay on land to observe religious practices, it was deemed necessary to allow them to eat meat, thus negating the need to be out in their boats.

It’s quite funny to think that Don Doroteo deemed an exemption was needed because his parishioners were either too religious, or not religious enough. It’s also amusing that fruits, vegetables and starches like rice and millet, staples of the local diet that would not have been subject to religious fasting, don’t seem to factor in at all to either of these stories (the stereotype of Filipino food being too meaty strikes again). Perhaps, just perhaps, we need to take the veracity of these stories with a good pinch of salt…

But as with all good stories that have somewhat dubious origins, the granting of the exemption from fasting during Holy Week has become embedded into local history and cultural traditions. It’s become quite a selling point for Bantayan, attracting visitors from across the country who want to have a bit of fun during Holy Week and eat the local meaty speciality: Bantayan lechon (roasted pig). For those who wish to be more solemn, there is always San Fernando in Pampanga, infamous for crucifying willing penitents.

**********

Read a bit more about the Papal Indult beyond what the stories say, though, and some of the facts start to unravel. For one thing, it is pointed out by many, including the museum’s curator, Kenneth Roger Molinar, that indults often provide only for time-limited exemptions; indeed, the Papal Indult held in Bantayan, is said to have allowed for the exemption to run until 1843. The exemption has, in essence, expired… not that it looks like anyone has noticed or minded.

The church authorities in Cebu seem to have conceded that they have lost this battle, though: the official quoted in the book Bantayan: Passion, Devotion, Tradition, sounds quite resigned when he says that meat eating during Holy Week is “a tradition that has been practised for over 100 years now, and it is tolerable.”

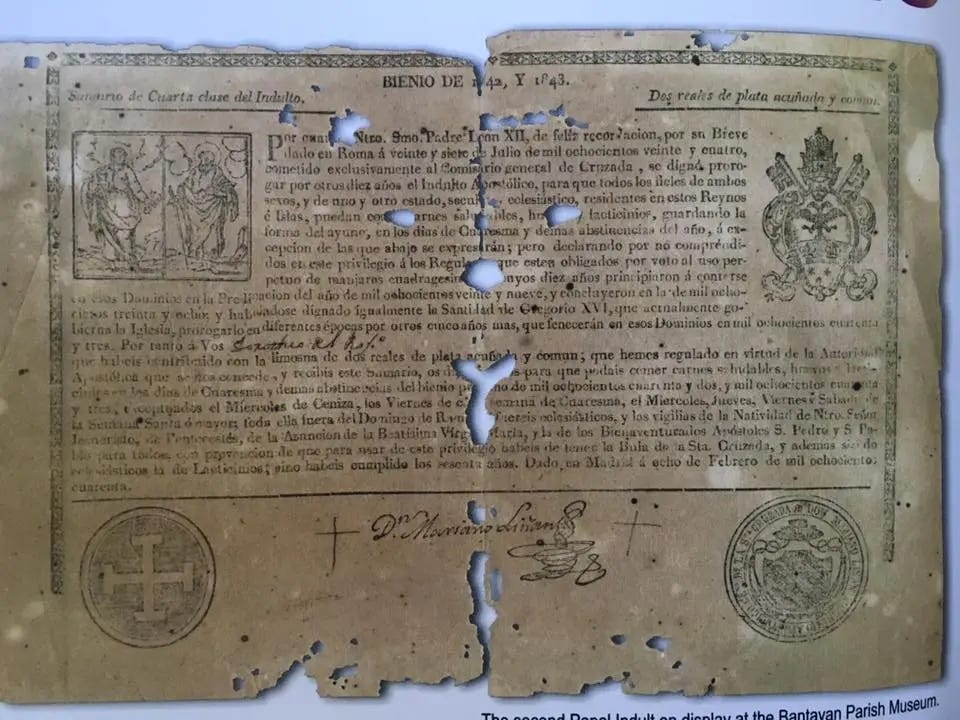

But more interestingly, it is also said that the exemption is just for one individual, and not the whole parish. According to Molinar, more thorough translations of the Spanish language document indicate that the exemption was granted just to Don Doroteo. You can just about make out in the image below the “Por tanto a Vos, Dorotheo del Ros.o” halfway down the document, on the left hand side. This was “due to the support he extended to the Holy Crusade”, in the unexplained words of the Cebu Daily Inquirer.

I found this rather traditionalist Catholic website that elaborates on this a bit further: what was actually granted was a bula de la santa cruzada, a Crusade Bull (a bull in this context being a type of public decree). Such papal bulls were originally issued to individuals who had contributed towards crusading efforts, granting them privileges, exemptions, or indulgences in return. Many Crusade Bulls were issued in relation to Spain and her empire, given her long history of fighting various heretics and infidels around the world, becoming a standard part of the Spanish church’s procedures and practices. It seems that by the 1800s, these Crusade Bulls had become another form of fundraising for a wide range of projects only tangentially related to crusading, like church repairs or educational efforts, something that was accessible to all. Essentially: donate some money to a good cause, get to eat meat on fast days.

According to a close reading of the Bantayan Papal Indult, in response to the ten-year ‘crusade’ preached in the Spanish realms in 1829 and extended until 1843, Don Doroteo contributed two silver reales. In return, he was granted the heavily-caveated privilege of eating meat and dairy on certain days of abstinence during the biennium of 1842 and 1843. Such a grant was drawn up in Madrid in 1840, with space left for the contributor’s name to be filled in, as and when it was given to them. No mention is made of Bantayan at all, and certainly something like this would not have crossed the desk of a papal bureacrat, let alone the Pope himself, in Rome. For all intents and purposes, tiny Bantayan remained unknown and unseen to church authorities in Europe.

That quite punctures and deflates the popular story, doesn’t it? The traditionalist Catholic website suggests that this all came about from a deliberate or incompetent misreading of the Spanish language document. On the other hand, Molinar, the Bantayan musuem curator, says “My theory is that… maybe Doroteo may have told someone that he got the indult or dispensation and then someone wanted to also have it, so it got replicated.”

(Side note: is this an early example of someone expressing the jokey critique ‘sana all’ / ‘must be nice, wish everyone had that’ sentiment?)

Rather than waiting for months or even years for such dispensations to be approved all the way back in Madrid and therefore risk missing out by the time the ‘crusade’ ended in 1843, did Don Doroteo perhaps take a shortcut and improvise a way for his parishioners to contribute and therefore benefit in the same way he did? Who knows.

**********

When I started researching this story, I thought to approach it from the view of exploring how European colonial authorities, both secular and religious, responded to the needs and whims of their subjects, even in the farthest corners of the world. That a small island in a distant colony could reach out to the metropole for a minor privilege, was very interesting for me. Exploring it in the context of the Philippines in the early 1800s could have also touched upon other very important topics.

Remember, the the loss of the South American colonies was still fresh and raw, and Spain was now governing the Philippines directly for the first time and trying to better understand how to handle a colony that had long-been left to its own devices. Against the backdrop of a growing reformist movement that called for the greater role of indigenous Filipino priests in the church hierarchy, as well as a nascent nationalist sentiment, the decision for the authorities in Spain to accede to a Filipino parish’s request takes on greater significance.

But as seen, this story did not quite transpire; the Spanish empire did not really extend any benevolence to the good folk of Bantayan.

It’s still a fascinating tale to tell, and not just because food is involved. Instead, I look to what it says about how religious practice moves across the world and is adapted and adopted. In Bantayan, a Crusade Bull providing a targeted and limited exemption has become the basis of a local tradition whereby meat, and especially lechon, is promoted during Holy Week and more widely Lent. It binds together the young and fervent religiosity of a native population still relatively new to Christianity, with the ancient and pre-colonial tradition of celebrating sacred events with a roasted pig. Strict Catholics may lament, like they have for many, maaany centuries (I saw many examples during my university studies in medieval history) that such syncretic practices are the result of an ignorant and incorrect understanding of the religion, but surely such adaptations are a reason why Christianity managed to be so successful and deep-rooted in so many different contexts.

In the Guardian article I linked about the crucifixions in San Fernando, a priest by the name of Robert Reyes criticises these local traditions and interpretations, asking “where were we church people when they started doing this?” It would seem, as in the case of the lechon exemption of Bantayan, that the church was already right there in the mix, adapting to the needs of the locals.

**********

Whilst I would love to share a recipe for lechon, I recognise that it may not be particularly practical for many people here; who has ready access to a whole pig, a fire pit and an entire day to set aside for spit-roasting?

Instead, here’s a recipe for Lechon Kawali, deep-fried aromatic pork belly, that is a just-as-popular way of consuming pork, and a heck of a lot easier to do in a home kitchen.

Lechon Kawali

This should be enough to feed 6-8 people, depending on how hungry you all are

2kg pork belly, ribs removed, and (if needed for easier handling) cut into 2-3 inch strips

1x head of garlic

1x birdseye chilli

2x stalks of lemongrass

4x stalks of spring onions

2x tbsp fine sea salt

2x tbsp ground black pepper

Additional salt as needed

Baking powder as needed

Fill a pot with water, just enough to cover the pork belly as a whole piece, and bring to a boil

As you are heating up the water, prepare the aromatics: mince the garlic, chop the chillies, bruise the lemongrass and spring onions

Add the aromatics, salt and pepper to the water

Once it has started boiling, add the pork belly and lower the heat to a simmer. Simmer for about 1 hour and 30 minutes

Once simmered, take the pork belly out and set on a rack and pat dry. You can reserve the liquid as an aromatic pork stock for later use. At this point, you can press the pork belly for an hour - skin down in a tray, with another tray with weights on top - to squeeze out some of the excess fats as well as to improve the texture and shape of the meat, but this is optional

Using a sharp needle or something similar, prick the pork belly skin evenly all over its surface, taking care not to pierce the meat underneath. Rub salt and baking powder into the skin (the baking powder’s alkalinity helps to break down some of the proteins in the skin, allowing for a better crisp), and place in the fridge on a rack, skin-up and uncovered, for at least two hours. Overnight is obviously best, but I’ve found two hours can work when you’ve only decided on the day that you want to eat lechon kawali

After drying the pork, take it out of the fridge and rinse off the excess salt and baking powder. Wipe the skin dry of any moisture

This is optional, but I find it helps to make little shallow slits with a sharp knife horizontally across the skin, about an inch apart. This helps to render a little bit more fat, but more importantly it makes it easier to portion the pork belly later without worrying about cutting the skin unevenly

In a deep-sided pot (or even a deep fryer, if you have one), add enough vegetable oil to deep-fry the pork. Bring the temperature up to 150c

Add the pork belly to the oil, skin-first. Be careful - there may be a lot of spitting oil and hot steam. You can cover with a lid if you wish to counter this. Deep-fry, turning the pork if you need to, until a good golden browness has started to develop, maybe after 10 minutes or so

Take the pork belly out and rest on the rack, as you get the temperature of the oil up to 190c

Once it has reached temperature, deep-fry the pork belly for an additional 5 minutes

Remove the pork belly and place it on a rack to cool, allowing for excess oil to drip off. Once cool enough to handle, chop or slice as required, following the slits you cut if you did so

Add some large crystal salt (Maldon salt for example) to garnish, and serve with sides and condiments of choice - my favourites are rice, ginataang gulay, spiced vinegar and toyomansi